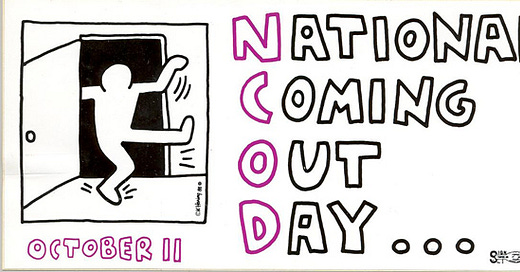

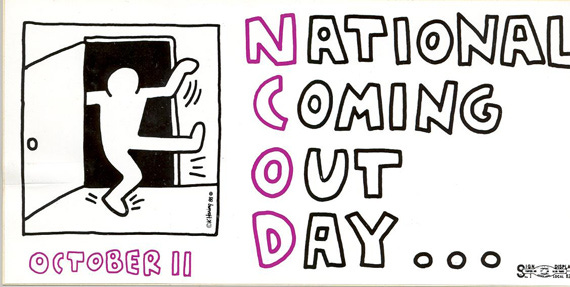

Tomorrow, October 11, is National Coming Out Day, a celebration of queer presence first commemorated in October 1988. Two activists, Jean O’Leary and Dr. Robert Eichberg, organized that first NCOD, with events in 18 states. One year later, in 1989, 21 states held NCOD events. By 1990, when all 50 states marked the occasion, its organizers founded a nonprofit with an executive director; it merged with the Human Rights Campaign Fund in 1993.

Organizers scheduled NCOD to mark one year since the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. At that time, the federal government had yet to allocate resources to the study of HIV transmission or to HIV/AIDS prevention or treatment, even as the death rate climbed exponentially. Many LGBTQ people and their allies lived with a sense of impending doom; their previously healthy friends were getting terribly sick and dying from an illness that had no known treatment. The world seemed content to watch them suffer. Overt homophobia among members of the administration of President Ronald Reagan kept the federal government from taking the issue seriously, let alone directing government resources to address it. The October 11, 1987 march, which drew hundreds of thousands of people, was a direct response to that apathy, an attempt to focus the nation’s attention on the plight of LGBTQ people in the United States. The event’s organizers wanted to end laws against consensual sodomy between adults, gain recognition of lesbian and gay relationships, and ban antigay discrimination. Combining declarations of queer love with pointed critiques of American politics and laws, the march was both celebratory and dire. Many marchers pushed ailing people with AIDS (PWAs) in wheelchairs. “For love and for life, we’re not going back!” a 1987 brochure declared.

“We of the U.S. gay and lesbian communities must bring an urgent message to the people of this nation: it is not we, but the threats to us, that endanger the entire nation and its values. Our enemies are pushing a familiar agenda of hatred, fear, and bigotry—against us and against freedom. They’re determined to deny us the right to make love, even in the privacy of our own homes.”

Whoopi Goldberg, Nancy Pelosi, and Jesse Jackson joined the 1987 march, an unprecedented demonstration of popular and political support for LGBTQ people. (Organizers also called for a reduction in federal military funding.)

By holding the first NCOD on the anniversary of the march, O’Leary and Eichberg intentionally connected the visibility of queer people to their demands for equal rights, safety, and freedom.

The idea of “coming out” is much older than NCOD or the 1987 March on Washington, however. As Abigal Saguy writes in her 2020 book, Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are, the language of “coming out” circulated among gay men in the United States as early as the 1930s, as a cheeky appropriation of “coming out into society,” a rite of passage for young debutantes making their first appearance in high society. Saguy describes “a 1931 news article in the Baltimore Afro-American [that] referred to ‘the coming out of new debutantes into homosexual society.’” But police harassment and official government discrimination over the ensuing decades soon dampened these celebrations of “coming out,” forcing queer people “into the closet” lest they face arrest, abuse, firing, or worse.

Growing militancy among LGBTQ activists in the late 1960s put the practice of “coming out” at the center of a radical political project. Coming out became not only a statement of personal liberation but an insurgent demand for equality. A group that called itself the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) had formed in the wake of the Stonewall uprising of late June 1969. Come Out! A Newspaper By and For the Gay Community was one of GLF’s first projects. (You’ll find full issues of this newspaper at the “Come Out Archive” on the OutHistory.org website, a phenomenal resource for LGBTQ history, founded by Jonathan Ned Katz and currently run by Professor Marc Stein, a prolific LGBTQ historian.) The inaugural issue, published on November 14, 1969, was a call to action:

“COME OUT FOR FREEDOM! COME OUT NOW! POWER TO THE PEOPLE! GAY POWER TO GAY PEOPLE! COME OUT OF THE CLOSET BEFORE THE DOOR IS NAILED SHUT!”

The founders of the GLF intentionally echoed the rhetoric of Black Power (“power to the people”) and of North Vietnamese resistance (“liberation front”) to Western imperialism, even as they called out other “oppressed groups” for discriminating against queer people rather than finding solidarity with them. Visibility was a radical proposition for queer Americans in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In encouraging people to “come out,” the GLF advocated for the transformation of a culture that not only presumed heterosexuality but too often forced queer people to conform.

The GLF collapsed in 1972, and many gay and lesbian activists shifted from radical protest to a liberal emphasis on working “within the system.” The meaning of “coming out” nevertheless remained politically potent. In 1978, San Francisco city supervisor Harvey Milk rallied support to defeat the Briggs Initiative, an effort to bar all gay people from public employment in California, with the slogan “Come Out, Come Out, Wherever You Are.” Not only was the idea of “coming out” once again linked to a political objective, but it was also once again a coded joke, in this case a winking reference to a song sung by Glinda, the Good Witch in the 1939 film Wizard of Oz, a favorite among gay men.

By the 1980s, coming out had an existential urgency to it. The organizers of the 1987 march and of the first National Coming Out Day in 1988 knew the stakes well. Dr. Eichberg himself died from complications of AIDS several years later (1995), at the age of 50.

With advances in gay rights and in HIV/AIDS care, that sense of urgency gradually diminished. In 2003, the Supreme Court ruled in Lawrence v. Texas that states could not prosecute consensual sodomy between adults. The 2015 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges struck down state bans on same-sex marriage. Massive infusions of government and private dollars into HIV/AIDS research led to breakthroughs like PReP, or Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, a daily medication that prevents infection with HIV. New treatments can lower the viral loads of infected individuals to undetectable levels. Being HIV-positive or a PWA is no longer a death sentence.

There is no question that the rights and protections we benefit from today reflect the work of generations of activists before (and, happily, often still among) us. But as anti-trans rhetoric heats up and the Supreme Court carves out exceptions to protections against antigay discrimination, it can be difficult to channel the optimism many of us felt in 2015. As I head into National Coming Out Day, I’m recalling not only activists’ battles against antigay hate but the joy of queer identity, from “coming out” balls in the 1930s to the humor of Milk’s slogan, and much else. This annual event marks not only a legacy of fighting against hate but a tradition of seeing LGBTQ identity as a gift, and that is worth celebrating.

My new book, FIERCE DESIRES: A New History of Sex and Sexuality, is out in print and as an audiobook! Get your copy today! And if you’re interested in having me speak to your organization, book club, or class, please reach out — my contact information is on my website, www.rebeccaldavis.com.

Some nice things other people have said about FIERCE DESIRES:

"[F]ascinating…[Davis] wants to show how the battles of today―over issues like gender nonconformity and reproductive rights―have antecedents that have been forgotten or suppressed." ―Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker

"Davis brings [the archives] to life in spellbindingly human detail...When viewed through the lens of history, sex is no longer a private act but a litmus test for political repression; the only way to know where we're going is to know where we've been." — Charley Burlock, Oprah Daily